Question Time on Climate Change with Vince Cable

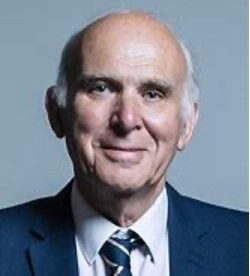

The Right Honourable Sir Vince Cable former Leader of the Liberal Democrats, Cabinet Minister in the 2010-2015 Coalition Government and former MP for Twickenham

Ten years ago, Stuart Mole, then Vice-Chair of the Commonwealth Association (CA), quizzed his former colleague, Vince Cable, about his involvement with the Commonwealth’s pioneering contribution to climate change policy as well as other global initiatives.

Some weeks ago, the CA’s current Vice-Chair, Bishahka Mukherjee, read the earlier interview and approached Vince Cable (also a former Secretariat colleague of hers) about his views on the current state of climate change policy in the run up to COP26.

MOLE/CABLE (2012)

SM: In the 1980s, as Special Adviser on economic affairs to Sir Sonny Ramphal, the former Commonwealth Secretary-General, you supported him during his membership of the Brundtland Commission, established by the UN Secretary-General to address mounting global environmental concerns. What are your views on the work and Report of this Commission?

VC: The Brundtland Commission was the first ground-breaking major multilateral initiative which dealt with global warming and climate change. Sonny Ramphal and Mrs Brundtland (former prime minister of Norway and chair of the commission) steered the commission towards a recognition that economic growth, which respects environmental protection, is essential to overcome poverty. Its 1987 Report, ‘Our Common Future’, introduced a new concept and definition of ‘sustainable development’ which integrates the importance of development with environmental protection. The Report has been very influential in directing the nations of the world towards issues related to environmental protection and the concept of sustainable development has become central to current global thinking about the environment and the economy.

SM: An expert group on climate change was commissioned at the Vancouver Commonwealth summit of 1987. How important were the findings and report of this group, which was chaired by the eminent British scientist Sir Martin Holdgate?

VC: The work of the expert group was truly pioneering at a time when the subject was not taken seriously. The group’s report, ‘Climate Change: Meeting the Challenge’, was a major intergovernmental input on the impact of climate change and sea level rise on vulnerable countries. We captured the emerging scientific consensus that there was a real problem, concluded that the world’s poor would be the ‘main victims’ of climate change and put forward proposals for preventive strategies backed by detailed analysis of the potential impact of sea level rises on Pacific atolls, the Maldives, Guyana and Bangladesh. A key outcome of the work of the expert group was the establishment of AOSIS, which continues to represent the interests of the 39 vulnerable small island and low-lying coastal developing states in international climate change and sustainable development negotiations. The report was also a significant building block for the first major UN conference on climate change, which led in due course to the 1997 Kyoto Protocol (seeking to curb emissions from industrialised countries in particular).

SM: What are your recollections of the drafting and adoption of the 1989 Langkawi Declaration on the Environment at the 1989 Kuala Lumpur CHOGM and that CHOGM in general?

VC: I recall the long drafting sessions at the meeting and was very pleased with two of its major outcomes. The first was the translation of the work of the Brundtland Commission on sustainable development into inter-governmental agreement, which in turn led to the work on climate change, including the Langkawi Declaration, as well as my involvement in the early stages of establishing the Guyana tropical forestry project. The second was the launch of the Hibiscus Fund, a private fund managing equities from a variety of Commonwealth emerging market stock exchanges. I spent a long time working with my colleagues Vishnu Persaud and Bishakha Mukherjee (and the International Finance Corporation in Washington) to catalyse this fund. It was immensely gratifying when this fund, one of the early emerging market funds, became operative.

I am also proud of the fact that the work I did with Commonwealth colleagues and experts, as well as with the Brundtland Commission, helped to lay the foundations for climate change policy.

SM: What are the prospects for achieving a greater international commitment to address climate change at Rio+20? And what part can the Commonwealth play in this process?

VC: The climate change debate has reached something of an impasse. While major emerging economies, including China, Brazil and India, broadly accept that they have a big role in curbing carbon emissions, they also face domestic pressures to maximise economic growth for poverty reduction. In major developed nations like the US and Canada, there is a strong political resistance to abatement measures. Resource-rich oil producers like Russia are not engaging. The main political victims of climate change – African countries where rain-fed subsistence farming is the norm as well as small states – are not powerful players. There is a powerful global self-interest in survival and a worrying lack of urgency and that trend continues.

SM: Thank you, Vince.

oooooooo

MUKHERJEE/CABLE (2021)

BM: Vince, what has changed since your interview with Stuart and in the last decade since Rio+?

VC: In the decade since I answered the above questions as Secretary of State, there are sources of both optimism and pessimism.

On the optimistic side there have been big advances in renewable energy technology at competitive cost. The big expansion of wind power in the UK, actively promoted by the Coalition government through the Green Investment Bank and electricity pricing reform, has become competitive in price with hydrocarbons – now, essentially, natural gas – and is becoming the dominant power source. In the transport sector, electric vehicles are taking off, including hydrogen vehicles in the heavy trucks field. However, there is a lack adequate charging infrastructure so far. There are comparable advances in Europe, Japan and parts of the USA.

On an international plane, the 2016 Paris Accord set specific and ambitious long- term targets for greenhouse gas reduction and was saved from collapse by the constructive intervention of Presidents Obama and Xi. China, as the leading emitter, also appears to have accepted a leadership role with ambitious renewable and nuclear power development, electric vehicles and carbon pricing, but it is still heavily dependent on coal.

The negatives centre on the remorseless rise in emissions and temperatures across the globe. Achieving the ‘safe’ level of 1.5 degree Celsius temperature rise looks very difficult especially as national commitments to ‘net zero’ are often vague and lacking in substance. Some important countries like Australia, Russia, and Brazil deny responsibility. The US opted out of the process under President Trump and there remains significant political resistance. Furthermore, the new ‘Cold War’ with China is preventing practical cooperation.

In the approach to COP26 it is not clear that governments can agree on a plausible net zero future, let alone implement it. But it is critical that agreement is reached and implemented. Time is not on our side and the world’s future is at stake.

BM: Thank you, Vince.